Historical writing on the Middle East and basically everything that could fall into the field of Islamic Studies is very often categorized as either modern or premodern. “Classical” is a common synonym for premodern, though they don’t fully overlap, and subfields that are particularly large and rich, like Ottoman Studies or possibly Early Islam, warrant the distinction of their own, more descriptive names. The dividing line is the colonial era: everything that came before is Other and foreign and dead, and everything since has shaped and is in conversation with the world as we know it.

While these labels might seem like a conceptual imposition by the [Western, Eurocentric, Orientalist, fill-in-blank] Academy, scholars of Islam have in many ways embraced the modern/premodern dichotomy. This is especially true of scholars of Islamic law for good and sincere reasons. As a religion and culture, Islam has for so long been so highly politicized despite the significant diversity that exists among Muslims themselves. The modern/premodern binary is a helpful tool in disentangling ideas, movements, and practices that are portrayed in media and political discourse as a single, homogenous tradition implied to be (and sometimes explicitly described as) backwards and illiberal. By contextualizing the 19th century origins of, say, Wahhabism or legal regimes in contemporary Islamic republics, the narrative of a rupture between modern and premodern versions of Islam, rent by the violence and destruction of colonialism, provides much needed nuance to discussions involving Islam, Muslims, and the Middle East.

For all of its useful and accurate explanatory value, the rupture narrative also functions to set premodern societies and concepts wholly apart from contemporary communities of scholars and readers. Yet this depiction of a lost and irretrievable past has implications for the ways Muslims can connect with their own history and heritage, and at worst facilitates portrayals of premodern Islam as a fantasy paradigm devoid of all modernity’s many ills. By taking a reactive position in defense of Islam as a tradition, the rupture narrative and its binary between all things modern and premodern takes for granted the framing of the initial charges — there is something ‘wrong’ with contemporary Islam, but it’s not caused by the religion itself. Rather, as with every other instance of inequality and oppression plaguing society, liberalism, capitalism, imperialism, nationalism, and Europe are the source of blame.

Perhaps such binary thinking is itself characteristic of modernity. We are either male or female, unless we identify as somewhere in between, in which case the majority of our peers code us as one of the two options. We are either foreigners or nationals, unless we come from more than one country, in which case we are asked to strategically declare a single homeland on forms and at checkpoints. Secularism and religion, East and West, Global North and South, privileged and oppressed, boss and worker — so many of the frameworks and concepts used to make sense of the world rely on the construction of black and white dichotomies. And despite recognizing and theorizing about ways such binary categories fall short of the nuance of our real, lived experience, we continue to employ them by default.

But what if we didn’t? “What politics are promoted,” the anthropologist Talal Asad asks, “by the notion that the world is not divided into modern and nonmodern, into West and non-West? What practical options are opened up or closed by the notion that the world has no significant binary features, that it is, on the contrary, divided into overlapping, fragmented cultures, hybrid selves, continuously dissolving and emerging social states?”1

In her new book Beyond the Binary: Gender and Legal Personhood in Islamic Law, Saadia Yacoob explores just such a possible alternative, arguing that early Hanafi texts assume legal subjects with no fixed, individual identity or agency. Challenging previous scholarship on gender and feminism within Islamic law, Yacoob speaks of legal personhood as both relational and intersectional, defined by a number of potential social factors and statuses that did not map cleanly onto sexed bodies. She writes, “The relational nature of legal personhood meant that individuals occupied multiple legal personhoods at the same time, depending on the different relations in which they were embedded…the intersectional configuration of social identities that shaped an individual’s legal personhood was not an essential aspect of an individual but instead dynamic and constantly shifting.”2 Thus rather than assuming that “gender was the primary category that structured power relations,” she shows how “different social identities were also mutually constitutive, meaning that neither man nor woman (nor free nor enslaved) carried meaning as a legal category outside their particular formulation in a particular legal person.”3

Yacoob discusses this dynamism in relation to slavery, showing the intersecting, fluid, and gendered legal identities a person might occupy as both slave or enslaver. Female slave owners at once had power over male slaves, disrupting patriarchal assumptions by severely limiting the latter’s autonomy at the hands of a woman, while also themselves subject to restrictions unknown to their male counterparts. For example, male enslavers were permitted sexual access to female slaves, though such behavior was impermissible for female slaver owners. Yacoob shows how much juristic discussion of femininity simply did not apply to a significant subset of women, like rules surrounding veiling and modesty. While free women, especially those of high social status, were expected to cover in public or remain in their homes, enslaved women were actively discouraged from veiling. Even slaves of the same gender might have vastly different legal statuses depending on their relationship with their owner — the title of umm al-walad, conferred to female slaves who had given birth to their owner’s child, came with special legal privileges like the right to manumission upon their owner’s death and prohibition from sale. Thus rather than a default legal identity based in gender, Islamic subjects displayed an array of relations in which gender was a central, but by no means sufficient or exclusive, category.

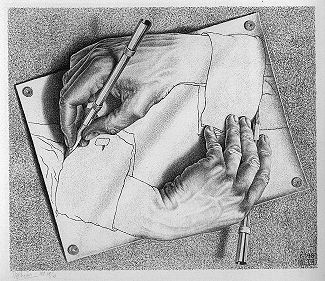

In her final concluding remarks, Yacoob references the ethical implications embedded in the dynamic subjectivity she sees present in Hanafi law. Channeling Asad, she writes that “this mutability of legal personhood viewed the human as always in the process of becoming rather than a fixed and static self…the focus on the relational self rather than the autonomous self of liberal thought…centers mutuality in ethics [and] is powerful in its recognition that our humanity is realized only through our relations to others.”4 The difference between relational identities and those in binary opposition cannot be overstated, as the latter are also “mutually constitutive” in a negative sense. As Asadian scholars have illustrated most potently through discussion of religion and secularity, both concepts depend on each other for definition and meaning as mutually exclusive opposites. Hussein Agrama memorably likens this relationship to the M.C. Escher lithograph of two hands drawing each other into existence. Neither concept can exist without the other, and they can never find common ground. In contrast, the relational subjectivity described by Yacoob is positive and constructive, utilizing “and” instead of “or” and “not.”

Taking Yacoob’s arguments one step further, if it is possible to see personhood as constituted by our ties to those around us, it is also possible to understand ourselves in relation to those who came before. Rather than the dichotomy of modern and premodern, as the rupture narrative would have us think, perhaps our humanity could also be more fully realized through seeing the connections we have to the past alongside the discontinuities. After all, as adeptly as Yacoob employs the concept of intersectionality to make sense of the ways jurists of the 10th and 11th centuries wrote about and understood gender, Kimberlé Crenshaw first introduced the theory to address contemporary debates within feminist and critical race studies only a few decades ago. Clearly, intersectional and relational conceptions of personhood and subjectivity are widely resonant. Instead of thinking about such identities as exceptions to the rule, what if, like the early Hanafi jurists Yacoob studies, we never assumed binary subjects as a legal baseline in the first place?

In a different work, Asad posits that “people, even in modern societies, live in multiple temporalities…what matters is that through a familiar medium, a totally unfamiliar sense…opens up a glimpse of another world that grasps one’s life.”5 An omnipresent force that structures both the real and conceptual avenues available for community and identity formation, law is just such a “familiar medium” by means of which, through its comparative study, we may catch a hopeful glimpse of possible futures. As historians, we should be invested in finding ways to tell narratives that do not shy away from the asymmetrical violence from which the modern world was birthed — and the devastating costs of that violence on peoples who still pay the price — while also not taking at face value the ideology of liberalism as the ‘end of history.’ Rather than emphasizing an untraversible rupture between premodern Islamic societies and the atomistic notions of personhood and belonging characteristic of secular, liberal modernity, the careful study of Islamic law might function as a mirror reflecting back ways of understanding ourselves forgotten but not lost.